So, you say that you are just not sure you can vote for a woman

The books in the picture are more than curiosities.

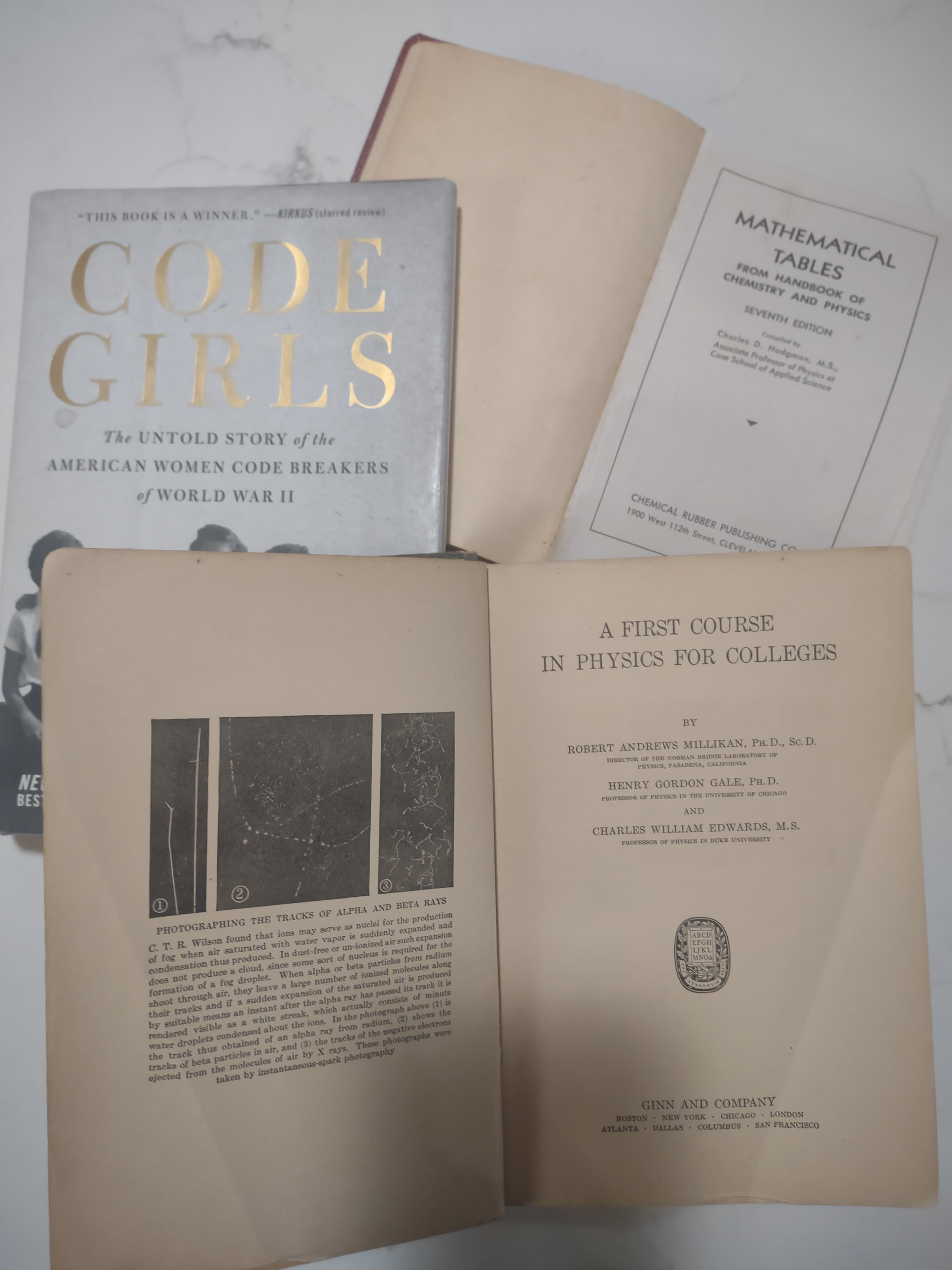

Two of them are pretty old. The physics textbook, from 1928, was my mother’s, and the Mathematical Tables her sister’s.

Their mother, my grandmother, also attended college.

The book, Code Girls, is much newer.

My stepmother was a Code Girl, recruited from college in World War II to break and translate German codes. After the war, she went back to school, studied music, and got a medical degree.

Her first practice was in Cary, North Carolina.

My father, coming of age in the Great Depression, always valued education. He believed it was the one thing that no one could take away from you – or that you could not lose. He extended this belief to the people who worked for him, helping them out to go to school when he could.

My sisters, my brother, and I all went to college. I don’t recall any discussion, ever, about whether or not girls went to college.

When I started at the University of North Carolina (UNC) in Chapel Hill, about 30% of the students were women. This was a huge increase from a few years earlier. For many years women had not been allowed to enroll as what is still often called freshmen, and many women started college at UNC Greensboro. Prior to the formation of the UNC system, the campus at Greensboro was named Woman’s College. The culture of attending Woman’s College extended into the 1960s.

All during my time at Chapel Hill, the number of women students increased noticeably from one year to the next. In 1978, two years after I graduated, women exceeded men in enrollment.

This surge in women students happened in many universities. It was a consequence of Title IX.

Now in most universities, colleges, and community colleges the enrollment is majority women. The number 60% to 40% is often given as the average, and there are places where admissions staff struggle to maintain even that balance.

This was a huge change in our country.

It is foundational to our economic success.

—

I want to step forward in time and shift the topic.

For this piece, I feel my point of view has some value. I have already admitted to a college education, and I am a white man, an old white man. For the largest portions of my career, mostly at NASA and the University of Michigan, I have been in positions of management, leadership, and influence.

I start with some observations from my career; they are anecdotal.

They are not meant to be revelatory, or to give readers any sense of “look what I discovered.”

Below, I describe, first, situations where, today, women scientists and engineers have numbers far more equal to men, than in my early career. They are, often, leading successful projects. Yet, there remain barriers that inhibit these projects from achieving full fruition and contributing to organizational goals. Using sexism to describe these barriers, however, does not tell the full story. There is a deeply entrenched resistance, fear of change, because, with change, we feel a loss of control over what we know how to do.

—

From the very beginning of my career, following graduation from UNC in 1976, I have had women as peer colleagues. In graduate school, at Florida State, the man who would become my advisor had taken his first woman student the same term I arrived. His admission of a female student was an exception to the norm. He glowed about his “experiment,” which he would say proved a great success.

When I took my first job at NASA, there were women in our research group. However, the number of women was not close to the number of men. Looking around our lab, there were a small number of more senior women researchers. Plus, it was obvious that the number of women in administrative assistant positions was large, and the number of women in management positions was small.

In my time at NASA, there were frequent discussions of sexism, challenges women faced that men did not face, and some proactive steps taken to reduce those challenges. Over time, women took positions in senior management, but middle management remained in the hands of men.

I jump forward 30 years, after we have had decades of majority women in universities.

One of the roles I took during my career was serving as a consultant to federal agencies. I was there because I had proved to have strategic skills thought useful in changing stuck, broken organizations.

In one of those consulting assignments, it was immediately obvious that much of talent, innovation, and product delivery was in projects led by women. Even more prominent, the organization’s management acumen was concentrated in these projects.

What I observed was that as these projects got closer and closer to fruition, they would be crippled in one way or another. Often, their supervisors, in middle management, would find reasons that the projects were not “ready.” For example, some sort of transition would be needed, and the time and resources for that transition would threaten the current mission. If the projects were critical to the organization, they might be appropriated by management—leaving the women who developed them demoted from team leader to participant.

Because women led so many of these projects, this pattern looked like sexism, and there was plenty of evidence of sexism.

There was, however, something even more fundamental. There were many—men and women both—who were vested in the status quo. They could, as individuals, get along, perhaps thrive, in the organizational quagmire they knew. They were content in continuing to do what they had always done. The status quo was a situation over which they had some control, perhaps a feeling of power.

This organizational culture, of doing what we know how to do, seemed even stronger than sexism. As women joined management, their presence could lead to change, but more often their presence perpetuated resistance to change – the clarity of the belief that we can only do what we have always done came into focus. It was too risky to try something else.

This institutional culture and structure works, disproportionately, to diminish the contributions of women. It is institutional sexism, that can, in fact, be carried out by individuals who are not, personally, sexist.

This organizational behavior assures that the organization remains stuck, the quagmire is sustained, and strategic goals are failures. It is frighteningly common.

Some of our sources of being stuck can be interpreted as a threat to traditional power structures.

Other sources, come from a deeply held belief of some men that they do not want to work for a woman – to recognize women’s contributions on par with their own contributions. Some men even lean into religious and cultural roles of women. They seem to fear what would happen if women were in charge of decisions, as if things would perhaps be unmanaged, simply not make sense, and slip into chaos.

I fear that this combination of sexism and the compelling urge to continue to do as we have always done is keeping us from electing women to our highest offices.

—

As I look around this world, which has been led predominately by men, it does not appear to be managed, to make sense, and to be without chaos. I see old men with armies carrying out grievances and ambitions. There are overpowered, outsized corporations, with their leaders shaping government and the economy in their vision, to their advantage.

I see a world that is structured to maintain the diminishment of the talents and skills of women, who since 1978, hold the majority of the benefits that education provide.

Our country does not realize the advantages of this resource, this investment.

It is like those stuck projects on which I consulted. As they got close to fruition, too close to power, ways were found to keep them from happening or they were systematically derailed.

The organization is more comfortable with failing than changing.

In this election, the choices between future and past, order and disorder, civility and incivility are stark. The seeming fear we have of women leaders and our uncanny drive to perpetuate the world that we know sickens me. I hear people talk about Mr. Trump’s reckless behavior, the criminal convictions, imperious promises, quests for revenge, and the promises to deconstruct institutions and break alliances and still say, “I am just not sure I can bring myself to vote for a woman.”

As a far less wordy friend of mine said, “Vote for the planet. Vote for decency. Vote for our children’s future. Do it.”